With four main image formats (JPEG, PSD, TIFF and EPS), choosing which image format to use is always a popular talking point with designers. Some say JPEG; others prefer PSD, many still use TIFF or even EPS. Here,

Dean Cook offers up some food for thought to help keep productivity up without bloating the size of your InDesign file.

With near-on three decades in the industry naturally comes experience. Still, if the 'if it ain't broke, why fix it' approach has always been a stable way of working, sometimes you need to periodically check if other image file formats offer a better way of working while meeting standards for commercial printing. Do you need to change formats because of evolving hardware, software and processes?

Firstly, let's turn back the clock

When it came to photo imaging in the '90s, there were only two main formats: EPS (Encapsulated Postscript) and TIFF (Tagged Information File Format). While EPS and TIFF worked with PostScript printers, the optional Adobe PostScript Level II software cost a small fortune compared to linear printers, which were far more affordable. As such, most designers opted to buy the cheaper linear printers and work with high-resolution TIFF images; however, the trade-off with productivity was huge.

Using high-resolution TIFF files within Quark XPress using computers with limited processing power and a small amount of RAM often bought it to a crawl. As a result, designers were forced to break down larger Quark XPress documents to just a few pages, which became more manageable. Alternatively, designers could employ a workaround solution. One example was placing separate low-resolution positional TIFF files supplying the high-resolution images to the printers to be swapped out at prepress. Unfortunately, this was not only a headache for many, it was time-consuming too.

Investing in a PostScript printer brought benefits such as accurate colour reproduction and greater productivity with larger multi-paginated files. Unlike TIFF, the high-resolution EPS file had a built-in feature that offered a low-resolution 8-bit colour positional image that could be imported and positioned within Quark XPress documents. It greatly helped to reduce the limited processing power and RAM required to handle the document and kept productivity up. The genius part about this process is that the EPS' high-resolution image data was only called upon when sending the artwork to a Postscript-enabled printer. It was an important factor, especially when working on multi-paginated documents. EPS also proved to be a robust file format that allowed you to build pages from cover to cover with speed and ease.

Towards the end of the '90s, the PDF file format came into sight. With a bit of experimentation, distilling PS (PostScript) files quite simply revolutionised how artwork was prepared for commercial print. Embracing a new way of working, the PDF encapsulated essential data, it offered excellent compression rates for print while still being able to supply lossless images. With prepress RIPs (Raster Image Processors) increasingly processing PDF files, EPS-based images for all PDF generated artwork proved to be a robust way forward.

Embracing PDF, I moved away from reprographics and prepress to become more involved with the design, production and construction of multi-paginated publications, which can be optimised for various output intents from a single InDesign file.

What about JPEGs and PSDs?

As widely known formats, JPEG (Joint Photographic Experts Group) and PSDs (Photoshop Documents) do a job, but they don't do it well from a production viewpoint. As with TIFF, they bloat the size of the Quark XPress/InDesign document, slows productivity, increases program crashes and can push through inherent issues to print. Okay, computer processing power and RAM are much better and way faster today, which lessens the speed aspect. However, bloated QXP/INDD files increase the risk of crashes as the program handles more embedded file information when, in fact, there is no need.

An image file format experiment

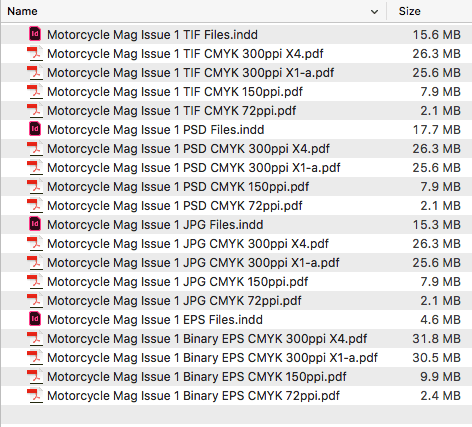

To find out what image formats would be best to use in InDesign, I decided to put together a little experiment. I created four identical 8pp InDesign files containing 20 CMYK images being the output intent and gamut of full-colour printing. The only difference was that each document had images saved as each of the four file formats: JPEG, PSD, TIFF and EPS.

Ensuring a level playing field, InDesign files were then 'Saved As' to remove inherent history information.

For this exercise, all JPEG images were saved with the quality set at '12 Maximum' to ensure a loss of image quality was minimised. TIFF files were saved with no compression, PSD files were natively saved, and EPS files were saved using Binary Code. The typical file size of one of the larger CMYK images was as follows: JPEG = 16.5Mb, PSD = 42.1Mb, TIFF = 45.4Mb, EPS = 57.5Mb. Don't dismiss these file sizes just yet.

Now, here's the point

So, if there is no apparent benefit in which file format to use when constructing artwork and exporting PDF files, what is EPS's productive benefit offer over its file format counterparts? It's not the image size of the source file. Nor is it the resulting PDF file size that is under the spotlight. For me, it's about minimising the InDesign document to maximise productivity while working with lossless images.

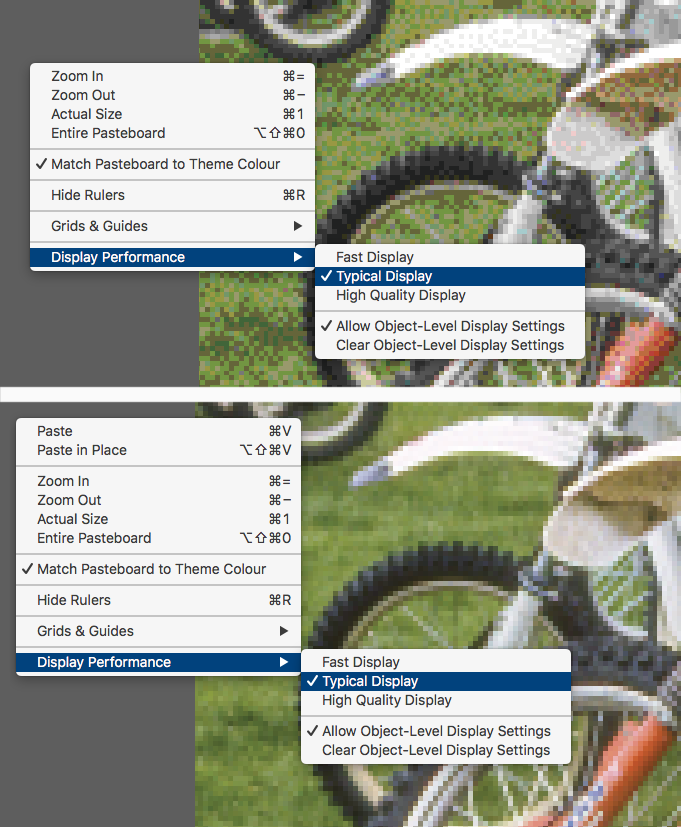

Let's look at the 8pp InDesign file size using different image file formats to show you what I mean.

Using JPEG images, the InDesign file size is 15.3Mb

Using PSD images, the InDesign file size is 17.7Mb

Using TIFF images, the InDesign file size is 15.5Mb

Using EPS images, the InDesign file size is 4.6Mb —

yep, it is under 5Mb — well under a third compared to other InDesign file sizes.

The low-resolution positional images offered by the EPS file creates a leaner InDesign file allowing for faster productivity.

So then, for longer multi-paginated documents, such as magazines, you can work with robust, lossless images that won't bloat InDesign files and slow down productivity yet can deliver compressed flawless lossless files for commercial printing.

Never again would you need to break down pages into several working documents to ensure your computer can still work.

Just a Quark XPress did, InDesign will only call upon the EPS file's high-resolution image data when required, such as exporting a PDF or printing.

Let's scale it up a bit

What would the InDesign file be like if I produced a 132pp magazine or a 276pp product catalogue containing some 4500 images? With JPEG-, PSD- and TIFF-based InDesign file sizes, there is a mean average increase of 350% compared to the EPS-based InDesign version. So potentially then the InDesign file of a 132pp magazine would increase in size from 83Mb to around the 300Mb mark, and my lean 332Mb 276pp InDesign file containing 4500 images could see it bloat to a whopping 1.2Gb. That's a lot of data, and any part of it could induce a program crash.

To summarise

While working with larger EPS files may sound ironic, it contributes to very lean InDesign files. It means working better, smarter, faster with no need to split documents across several smaller paginated InDesign files either.

Your choice

Ultimately it does come down to personal preference. For me working with large multi-paginated documents, I would never use JPEG in artwork for print ("shock, horror", I hear you say!). You see, it's not about preserving data storage; GigaBytes are cheap. It's JPEG's damaging lossy compression that causes irreversible loss of quality in images, but it also bloats the InDesign file by some way, too (350%?). Replicating image quality and definition in print is key, rather than how much space images occupy on your hard drive.

TIFF and PSD are both very much on the same level as lossless formats. However, I am sure the majority will agree, PSD easily takes the lead out of the two as you can import native layered images directly into InDesign. It is convenient if you need to work in layers, and in these instances, PSD is also better than EPS,

but

it will contribute to the bloating of your InDesign file. So, it's better to use PSD files only if and when you need to.

Do I work with TIFF? Well, yes, I do, but only for bitmap/lineart and monochrome images. This format allows me to colour up once positioned in the InDesign document.

For the vast majority of flattened images, the lossless EPS is very much still the most solid format for print production. Yes, it requires more storage, but it's how the low-resolution positional help to keep InDesign's working file very lean, in turn, speeds up how it works with you. Being a sturdy format, EPS is quick to work with, quick to export and encountering technical issues is extremely rare.

The CMYK binary-coded EPS file continues to work beautifully today as it did at the start of my career. I still ardently remain that EPS is my preferred file format for flattened colour images for production and commercial printing. Adobe's Photoshop EPS is a more powerful format than you think.